CDR Policy Roads Less Traveled

Paths to focus on for carbon removal policy in the wake of a US election

“When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves”

- Viktor Frankl

I wrote at the start of this Substack that it would be a series about carbon removal covering insights about carbon markets, workforce and policy. Today in the wake of the US election outcome, I am going to take on that third topic - policy - with some quick takes on what the US election in November 2024 might mean for CDR Federal and State policy efforts. As much as I’ll write about policy in this post, I can’t avoid the politics of the moment. My instinct is that while US Federal climate policy per se will likely take a step back or two (or three…) in the incoming administration, a reframing of policies that advance carbon removal specifically as an economic driver would be a path forward.

First, some first impressions of what’s possible at the Federal level in the United States. I’ll keep this as specific as I can to carbon removal since there are many, many platforms better equipped than I am to speak to broader policy impacts.

The clearest risk to support for carbon removal comes in how the Trump administration might restructure the Department of Energy, specifically the office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management (FECM) which has been administering the DAC Hubs and other carbon removal programs. Notably, the DAC Hubs in particular were authorized and funded by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), rather than the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) which passed on a partisan vote. So it is possible that the bipartisan nature of the BIL funding would insulate programs it supports from being scaled down. The tax provisions of the IRA - in particular 45Q - might be subject to repeal, under a scenario of unified Republican Presidency, House, and Senate.

Beyond the Direct Air Capture programs at FECM efforts the department has recently taken action on marine carbon removal (mCDR), enhanced rock weathering (ERW), and biochar might be subject to change as well. Look additionally to new appointments at USDA - which administers US Forest Service and Natural Resources Conservation Service, as well as Commerce - NOAA and National Institutes for Standards and Technology - which impact these methods of CDR as well.

For Congressional action, the upcoming Congress at the time of this writing (November 11th 2024), appears to have a thin Republican majority in the House, while Republicans will take control of the Senate. While a comprehensive climate bill (‘IRA2’) is off the table, other policy avenues are open which would require bipartisan support. For instance, the 2018 Farm Bill will be up for renewal, with US Congressman Don Bacon (R-Nebraska) having supported bipartisan climate friendly agriculture legislation in the past likely playing a key role. Biochar, ERW, and soil carbon sequestration advocates would take note.

For DAC advocates, permitting and the intersection of DAC and energy policy would be areas to watch. Any efforts to reform carbon dioxide pipeline permitting (more on this below) would be a start. Also, the possible re-election1 of Michelle Steel (R-California), who has supported bipartisan geothermal energy legislation, suggests that advancing projects using a geothermal Fervo Energy’s new project will harness the earth’s heat as an energy source for DAC could have support.

Since Federal CDR policy may have to be meted out piecemeal, carbon removal policy advocates could then look to state governments as areas to advance policy ideas. I will recap some of the election results here, outlining particular actions to take in specific cases.

Washington State: Ballot Initiative 2117 failed resoundingly, with 62% voting “No”, thus preserving the state’s Cap-and-invest system for selling emissions allowances and reinvesting the proceeds into the State’s economy. A wide variety of organizations contributed to the “No on 2117” campaign, including corporations such as Amazon, Microsoft, REI, and British Petroleum (!) aligned with several unions and climate affiliated civic organizations. Key to the messaging was the economic benefit to the state in retaining the cap-and-invest system; additionally, there is evidence that the fiscal impact of the state losing $3.8 billion in revenue from 2025 to 2029 if 2117 had passed was persuasive to voters.

What it means: Revenues from the cap-and-invest system will continue apace to flow to the state’s accounts, which are set up to collect and disburse auction proceeds to advance the clean energy economy. For Carbon removal, this includes state grants that CDR companies are eligible for under the Clean Energy Fund.

Going forward, Washington can now pursue linkage in its Cap-and-invest system with California and Quebec’s cap-and-trade systems, as directed by the state legislature in the spring of 2024. How carbon removal credits integrate into this remains to be seen, however. First steps include the Department of Ecology writing a study - slated for completion and release in June 2025 - covering “the extent to which carbon dioxide removal is needed to meet Washington's emissions reduction targets”.

South Dakota: Carbon removal pipeline enabling Referendum 21 failed, with 60% of South Dakota voters rejecting a measure that would have made constructing carbon dioxide pipelines easier in the state. Opponents had argued that passing the referendum would have canceled local governance and removed protections for landowners.

What it means: Envisioned as a CO2 transportation pipeline for ethanol-based CO2 capture, DAC developers should take heed to consider local community concerns surrounding possible similar CO2 pipeline efforts.

California: California voters approved Proposition 4: a $10B state bond to be distributed to counties, local governments, and Native American tribes to support a wide variety of projects, including clean water security, reducing risk of flood and wildfires, and also improving marine ecosystem regeneration in aid of climate resilience.

CDR angle: With $1.5B slated for wildfire risk reduction, including forest thinning, California biochar producers could see a greater abundance of feedstock for pyrolyzing operations. It might also improve offtake for the biochar itself, which has uses for wastewater remediation. For marine CDR companies, $890M of the $10B is marked for coastal projects; project that improve water quality and promote coastal resilience while also removing atmospheric carbon dioxide might benefit.

Louisiana: 73% of voters approved a constitutional amendment that revenue from state renewable energy projects, such as wind power, can be diverted to coastal resilience measures

Implication: Similar to California, to the degree that marine CDR projects - particularly in a coastal location - can add to the state’s ability to buffet against hurricanes, floods, and sea level rise, this would be a benefit.

Massachusetts: This is not directly election related, but noting that the state legislature will consider an Economic Development package in a special session, which contains many climate and lean energy provisions which would be important for CDR. The House and Senate had each separately passed their own bill and to agree on a common bill to send to Governor Healy for signature before the current session ends on December 31st.2

So what kind of pathways are best for policies to support carbon removal?

In my view, reframing the discussion of carbon removal policy in the United States as an economic development measure and not a climate measure could lead the way to successful growth of the industry.

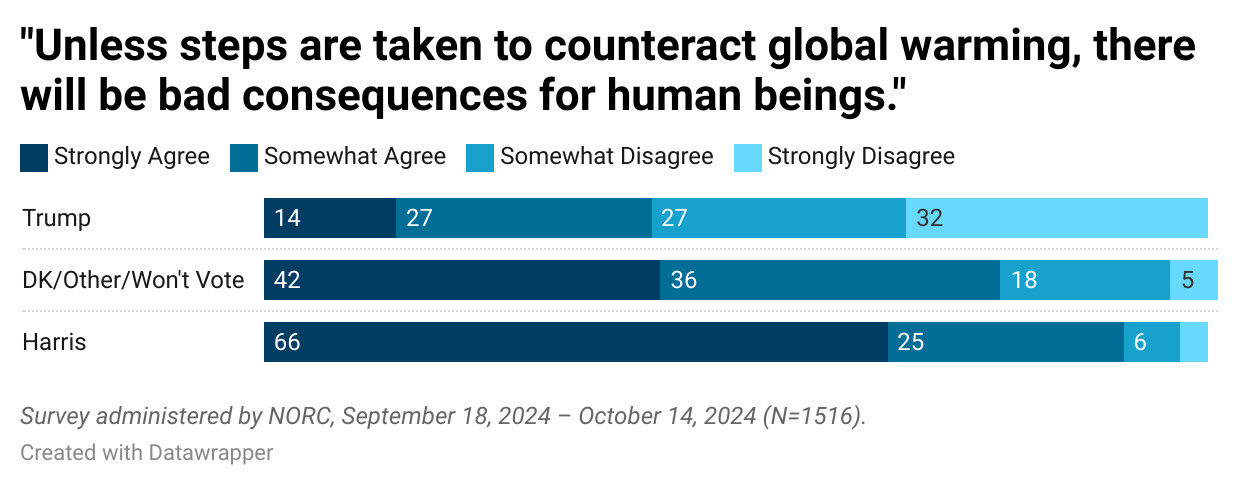

Why? For one thing there is motivation to do something about climate. Voters - and surprisingly a high percentage (~40%) of Trump voters - at least somewhat agree that climate change is a problem:

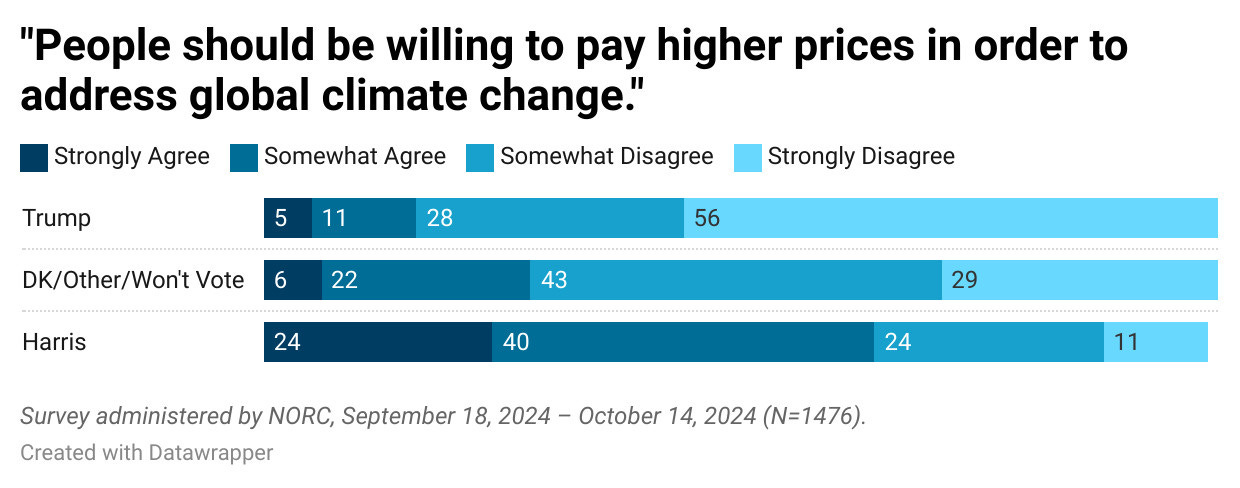

But - even among some Harris supporters (~35%) - American voters are not willing to pay for measures to counteract its effects:

Carbon removal projects that show an economic benefit beyond the action of removing excess atmospheric greenhouse gas will be a winner in the policy environment that will likely emerge from the 2024 US election season. The ability to show tangible benefits to people in communities, in the form of providing valuable products or services, or well paying careers - not just project-based jobs - for people who are struggling in an economy that they (fairly or unfairly) perceive to be still ridden with inflation or unemployment. And that might affect how C-suite and corporate sustainability managers perceive the need for climate action, and by extension carbon removal, as investor Susan Su mentions here. The perception of the state of the US economy among Americans has diverged from how the actual economy is performing since the COVID pandemic. This suggests that policies that underscore the economic benefit to voters would find a favorable reception among government leaders at any level.

While there may be limited pathways forward at the Federal level, State and local efforts at CDR policy offer a potentially meaningful way to support the industry. Even if policies are not specifically titled ‘carbon removal’, policymakers can include CDR alongside general economic development efforts - and make a difference in their state, county, or municipality. Respecting the interests of those communities - particularly at a local level - is paramount, as evidenced by the South Dakota measure above. Project developers who are in touch with the communities where they operate can consider how to meet the needs of those where they operate. And that’s important: especially in this environment, building political support starts at the local level.

This can move the conversation away from carbon removal being perceived as an expense imposed from outsiders, and rather as a source of revenue generating activities integrated into the economy and society, and coincidentally happen to draw excess greenhouse gasses out of the atmosphere.

Venture capitalist Vinod Khosla wrote over a decade ago that for ‘cleantech’ to succeed it has to be perceived as ‘maintech’ - that it integrates within the industrial base as a natural progression of technology in the minds of customers. Reframing the conversation about carbon removal from a climate technology dependent on specific climate policy to a ‘maintech’ solution that integrates with economic policy is a step forward in an otherwise daunting national political environment for climate in the United States.

Jason Grillo is a Co-Founder of AirMiners. The opinions expressed in this writing are the author’s own and do not reflect the position of any employer.

This post appeared originally on the blog of the Institute for Responsible Carbon Removal at American University

Follow up: Republican Michelle Steel lost to Democrat Derek Tran, so will not be representing California’s 45th District in the upcoming Congress.

Postscript: Governor Healy signed the bill into law on November 20, 2024.